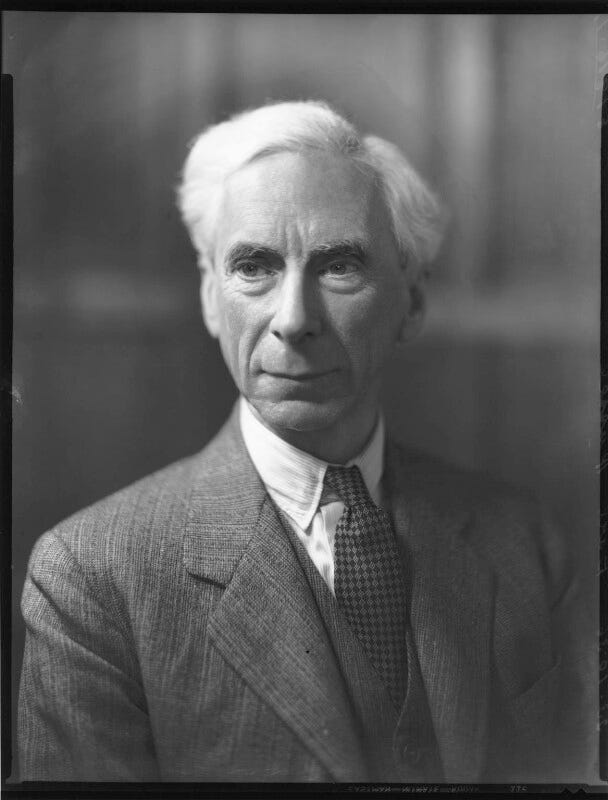

Mathematician and philosopher Bertrand Russell, born in 1872, recalling in this interview that his grandfather knew Napoleon, reflects on how the world had changed. Lord Russell’s upper-class upbringing so permeates his speech and manner that it’s surprising Monty Python never did a sendoff of it. Getting past that, however, Russell’s wit can charm even those who disagree with him. That’s why I put this post in the Free Speech section of this Substack. Common-sense animates every element of his philosophy, yet taken together, it is a bundle of contradictions.

The interviewer, Romney Wheeler — who does a great job of asking concise questions that stimulate Russell’s thoughtful answers — asks him who was the most influential modern philsopher. ‘Marx’, says Russell, ‘though I would hardly dignify him with the name of philosopher’. And what sort of philosophy would bring the world to a state of happiness? (This was back in the day when it was not so unusual to seek in philosophy a guide to happiness.) Here (at 27') Russell’s answer sparkles with brilliant simplicity:

‘If a philosophy is to bring happiness, it should be inspired by kindly feeling. Now Marx is not inspired by kindly feeling. Marx pretended that he wanted the happiness of the proletariat. What he really wanted was the unhappiness of the Bourgeois. And it was because of that negative element, because of that hate element, that his philosophy produced disaster. A philosophy which is to do good must be inspired by kindly feeling and not by unkindly feeling.’

There he neatly summarizes what’s wrong with Communism and Marxism, and why its proliferation has produced so much misery. Not only economic mismanagement, not only suppression of freedom, not only glorification of the state, but unkindly feeling is in the DNA of Communism. And — here is one of those contradictions — in its superficially benign offshoot, socialism and Fabian Socialism of which Russell was an adherent.

World happiness, Russell says in another part of the interview, requires three things: (1) World government that monopolizes armaments so that war between nations becomes impossible; (2) Approximate economic equality so that poor nations do not make war on rich nations; and (3) Approximately stationary population. All very logical. And in all, blissful unawareness of the unanticipated consequences of these unimpeachably good intentions. In fairness to Russell, no one in those hopeful days of 1952 could foresee 70 years later the medical tyranny of the World Health Organization, the alliance of UN peacekeepers with child-traffickers and terrorists, the grooming of freedom-suppressing officials by the World Economic Forum. Nor could anyone foresee the massive transfers of wealth from the poor and the Marx-despised middle-class deplorables of rich nations, to the oligarchs of poor nations, extracted by such devious methods as carbon taxes and foreign aid. Those are the present-day realities of world government and the commendable desire for approximate economic equality. Far from averting war as Russell wished, these policies have produced a new kind of warfare, waged by globalist forces against ordinary people, with cybernetic, psychological, and biological weapons. More about that in a subsequent post.

Now to the third element of Russell’s recipe for world happiness: Stationary population. Food supply being constant, with population multiplying — Do the math, he might have said. His actual words are (uncharacteristically) less direct: ‘That means that unless people are to be very poor, there must not be many more people to be fed than there are now.’ In 1952 about two and a half billion people lived on the earth. Not a word about how world population is to be made ‘stationary’, how exactly the preferred population number is to be achieved, nor is there any mention of who (WHO?) is to decide the fate of excess humankind. World population is now (mid-2024) about eight billion. Bertrand Russell’s words have been taken up and echoed by computer programmers (whom I would not dignify with the name of mathematician) and would-be philosophers since, starting with the Club of Rome in 1972, on down to today’s techno-utopians who deploy opaque computer projections to urge killing off a few billion of us — to save the planet, of course. More about that also in a future post. For now, it’s notable that today’s eugenics advocates are less squeamish than their forerunners about the methods they would use to accomplish their ends. And the bio-weapons at their disposal are already deployed.

Bertrand Russell’s brilliance is undeniable. Unlike today’s planet-saving number-crunchers, he would have room in his capacious mind for a second or third thought about the actual consequences of world government, coerced wealth transfers, and population control through medical carnage. A philosophy of happiness originating in kindly feeling could do no less.