Subcontracting the Wet-work

Why it fails

March 19, 2025

Remote-control warfare creates a new class of war-gamers, descendants of the cigar-chomping armchair generals moving toy soldiers around on large-scale relief maps. Today's remote controllers likely as not include representatives of the fairer sex, out to prove they can be as brutal as men. The war in Ukraine brings them a risk-free vicarious thrill of violence, rather like that of a video game.

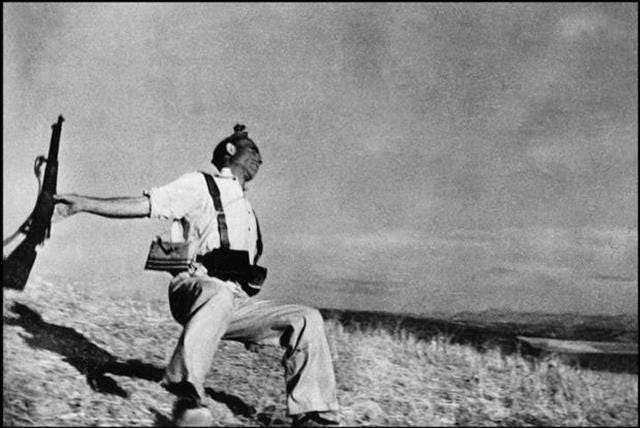

Robert Capa's 1936 photo, one of the most memorable images in the art of war, of the fall of a Loyalist in the Spanish Civil War depicts the violent death of a single soldier. Like the Unknown Soldier, his death symbolizes the fate of millions ground into dust by geopolitcal rivalries. This battlefield reality is worlds apart from the official domains of self-appointed armchair generals and their cheerleaders, who rarely if ever call upon themselves or their families to give their lives for the causes they so ardently advocate. In real self-defense, leaders and led are one, all-in for mutual protection. This is the foundation of platoon or village solidarity under mortal threat. In movies, video games, and remote-control warfare, by contrast, the button-pushers hire others to do the actual killing, known as the wet-work.

The Perfect Murder

Wealthy financier Steven Taylor (Michael Douglas), his financial empire collapsing, hires a hit-man to kill his wife Emily (Gwyneth Paltrow), engineering a bailout with her inheritance. The hit-man is failed artist David Shaw (Vigo Mortensen) of the meaningless-splash persuasion (an apt comment on the character of contemporary art). Shaw subcontracts the wet-work to an associate who botches the job, and himself gets offed, as in Hitchcock's Dial M for Murder on which it is loosely based. Emily survives and calls the police, who find the circumstances suspcious, which is not good news for Steve. Shaw, nothing daunted, demands $400,000 from Steve, as previously agreed. Steve, barely restraining his outrage at the injustice of this demand, protests 'You didn't exactly fulfill your part of the bargain did you'. Shaw says 'So what'. Steve, the reality of his predicament slowly dawning on him, summons all his gravitas to ask 'What do I get out of it?' Shaw: 'Time out of prison, old boy. Can't beat it with a stick'. Such are the perils of contracting-out the wet-work. Steve later tracks Shaw down and knifes him, his do-it-yourself violence making him oddly a more sympathetic character.

The car dealer in Fargo, Jerry Lundegard (William H Macy), had married the boss's daughter, but is still desperate for money. He asks an ex-con in his employ to find someone to kidnap his own wife for ransom, thinking that would pry loose some funds from the flinty father-in-law. The kidnappers are taken aback by Jerry's plan, but soldier on since he's paying. One of the hired kidnappers (Steve Buscemi), normalizes it with bureaucratic memo-speak: 'You're tasking us to perform this mission'. Jerry hasn't fully vetted these guys, relying on the word of an ex-con to vouch for their fitness for the task. Obsessed with his own objective, he ignores all the numerous ways this deal can go wrong. The movie explores a few of these. The other kidnapper kills a policeman who stops their car to inquire about a traffic violation. The planned ransom payment devolves into another unplaned murder, and a bullet wound to one of the kidnappers, who not unreasonably thinks he deserves some hazardous-duty pay in the form of a larger share of the loot. Instead he ends up in the wood-chipper. Meanwhile Jerry flees an interview with Sheriff Marj (Frances McDornan) and is later humiliatingly hauled in when his role as the perpetrator of the kidnap scheme is exposed. Having commissioned others to do the unpleasant tasks, Jerry Lundegard must take the consequences he was so loath to anticipate.

You Can't Make This Up: From Movies to Real World

Now consider an analogous situation: Those who command military forces to do their killing for them, for geopolitical advantage, national glory, enslavement, theft of natural resources, or other worthy causes. Those who 'stand for Ukraine' pay for the slaughter with their taxes (and with other people's taxes). At least the financier who hires a hit-man to kill his wife, and the car dealer who retains a pair of low-lifes to kidnap his wife, use their own money to pay for these crimes. Actually fighting, risking exposure to mortar fire, howitzers, drones, missiles, bombs, incineration, collapsing buildings, and other normal conditions of war resulting in death or grievous bodily injury — that's not for the 'stand-by-U' brigade. They'd rather have 18-year-old boys — someone else's son or husband or father — sacrifice themselves. For what, exactly?

Judging by actual results, for the personal fortunes of Ukrainian oligarchs, American politicians, and suppliers of said missiles, rifles, tanks, drones, etc. Ukainian President Zelynskyy admits that 58 percent of the $350 billion U.S. taxpayers sent Ukraine is 'missing'. The non-partisan General Accounting Office assesses 'DOD doesn't have clear guidance for tracking equipment deliveries, and its delivery data may not be accurate', and doesn't know whether equipment as been delivered, lost, or diverted to unauthorized destinations or purposes. U.S. taxpayer gifts to Ukraine through USAID 'are not comprehensively assessed and documented relevant to fraud risks'.

And now (March 2025), in the latest extension of this tragico-farcical conflict, British and French bankers plan to control Ukraine's mineral and agricultural resources. Perfidious Albion and its cross-Channel partner, unwilling to pay for it themselves, wish to subcontract America in the role of tough-guy enforcer, because, after all, the Yanks are good at that sort of thing, it boosts their self-esteem to imagine they're saving Europe again. President Trump is onto them, understands their game, and is having none of it. Whereupon the Russia-collusion hoaxsters deliver an encore performance, right on cue from the Europeans to their spokesmen in the Senate and the media. Expect the Steele dossier to be updated whenever its author comes out of hiding.

Like Fargo's Jerry Lundegard, Messrs Starmer and Macron, and the Ursuline ladies' auxiliary, haven't considered any of the numerous ways their plans can go wrong. First, what exactly are their plans? They or their predecessors signed several Minsk Agreements to stabilize borders and eject foreign armies, but these were never implemented. Bellicose utterances from a series of British Prime Ministers (notably Johnson and Starmer) toward Russia have only made them look ridiculous in light of the relative size of the forces at their command. Their plan, though never articulated, seems to be to put token numbers of their soldiers in the line of fire, hoping the inevitable casualties will revive American interest in deploying hundreds of thousands of their own young men. The last time that worked was 85 yars ago in the runup to World War II. President Trump's response to the EU suggestion of futher U.S. involvement is to evoke the 'big beautiful Atlantic Ocean', rejecting their idea with unaccustomed politeness. Starmer and the Ursulines also seem blissfully unaware that pitting two nuclear superpowers against each other, as they are wont to do, risks a nuclear World War III in which billions would lose their lives. This proves how tough they are, in their own estimation. Yet their belief (whether correct or not) that they will be insulated from the consequences of their policies inevitably introduces error into their calculus.

Unanticipated Consequences

Robert Merton's 1936 essay, 'The Unanticipated Consequences of Purposive Social Action', analyzes how and why plans fail to achieve the objectives desired by their authors. The essay was published during a period when planned societies ranging from Soviet to Fabian-socialist styles of top-down governance attained worshipful currency among Western intellectuals. Their alliance with statist-oriented officials cemented the nascent administrative state into the place it enjoyed until very recently. Office-holders enthusiastically welcome academic rationales of their supposedly superior wisdom and expertise, while central bankers avidly heed Keynesian economists exhorting them to spend money that isn't there. Merton's essay reminds us of the many ways that such models can and do fail in real life. It applies to all purposive social action, of which unprovoked warfare and civilian murder-for-hire are special cases.

If we apply Merton's essay to current cases, what stands out most prominently among the reasons why plans fail is obsessive focus on a desired outcome. Steve the financier, Jerry the car salesman, and Keir the statesman completely disregard all elements of the situation besides their own preference, as if nothing else mattered or even existed. Steve doesn't even imagine that his hit-man won't follow his instructions to the letter. There is no place in Jerry's thought-system for the violence of the criminals he engages to spin out of control. And for the armchair warriors, the interests of other parties besides their own chosen hero of the moment not only don't matter; their radar screens don't even register the presence of such interests.

In international affairs, failure to recognize the interests of other nations inevitably has unanticipated, often fatal consequences — for those on the fields of battle including cities. Whatever the cover story may be, deploying an army next door to another nation, with missiles that can strike its capital in six minutes, must surely trigger a response aimed at removing those threats. Failure to anticipate such a response, or willful ignorance of it, brings inevitable military defeat and needless loss of life.

Related to obsessive disregard are 'fundamental values', as Merton puts it, 'not concerned with objective consequences of actions [taken] but only with the subjective satisfaction of duty well-performed'. The purpose of such purposive action might today be called virtue-signaling, or the public display of beliefs (whether true or not) signifying membership in an alliance. The actual consequences, however destructive they turn out to be, are peripheral to such impulses. Hence the flag-waving by Congressional Representatives and media-besotted citizens who a couple of years earlier could not place Ukraine on a map.

Merton recognizes in this essay that perfect foreknowledge is neither possible nor necessary, as it would stifle action. Uncertainty is always a given, but 'immediacy of interest', as he calls it, practically guarantees unforeseen effects. Lacking time to anticipate what may happen, or even to gather information pertinent to alternative courses of action, the imperative demand to 'do something' deteriorates into habit. The assumption that actions leading to success in the past will always, everywhere, and under all conditions continue to do so rules the day. Steve's financial legerdemain will always conjure more money out of thin air, he believes — a belief shared by real-world central bankers whose antics produce debt in the tens of trillions of dollars. Jerry the car dealer believes his talent for bamboozling customers will carry over into fooling Sheriff Marj as well. Both Steve and Jerry learn the hard way that their habitual responses don't always work. Similarly in international affairs, habitually invoking the ghosts of World War II to cobble together an alliance brings unanticipated consequences. The vastly different conditions prevailing today, such as shortages of weapons and human cannon fodder, lack of popular support, and general unwillingness to divert financial resources unproductively, invalidate the habitual model.

The Human Factor

From all this, there's one major reason why subcontracting the wet-work fails — the human factor. Sooner or later, the people relied on to do the actual fighting or killing develop their own volition, which may differ from that of their commanders or clients. Lack of adequate information, to be sure, handicaps any mission. But it's the unpredictibility of human behavior in the field that most interferes with the purposes of higher-ups.

Many solutions of this problem, beyond the scope of this post, have been devised by organizational and philosophical theorists. These involve various schemes for aligning the needs and wants of those who do the work with those who direct it. Large-scale organizations do in fact succeed in many of their endeavors, despite uncertainty, inadequate information, inability to anticipate consequences, and so on. Their success, when it occurs, results from meshing the human factor in small groups with the overall organzational mission; in this way gathering and focusing the energy of all which would otherwise be randomly dispersed.

It's an open question whether artificial intelligence will enhance or degrade the human factor in society. The prospect of getting answers to questions without limitations of time or computational capacity is enticing. Many unanticipated consequences, and even unimagined consequences, will suddenly loom into view, along with uncountable descendants of those consequences. These are already leading to momentous discoveries in every field of human endeavor. At the same time, techno-utopians of the globalist persuasion seek to use artificial intelligence to remove the human factor, since that is the greatest source of uncertainty and unpredictibility. If people can be turned into trans-beings, educationally indoctrinated, implanted with thought-control chips, genetically modified with injections purporting to prevent disease, or inundated with psychotropic media, then uncertainty about consequences could be minimized. So too would a lot of fun and spontaneity.